Assad Says Syria Has Held ‘Meetings’ With US

Blinken says US is 'engaged with Syria' in efforts to free missing journalist Austin Tice

The United States is "engaged with Syria, engaged with third countries" to try to bring detained journalist Austin Tice home, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said Wednesday. "We are extensively engaged with regard to Austin, engaged with Syria, engaged with third countries, seeking to find a way to get him home.

Parents of Austin Tice, journalist held in Syria since 2012, are "100% certain" he's alive - "The Takeout"

The full interview with Marc and Debra Tice will be available Friday morning on "The Takeout" podcast and will air on CBS News at 6 p.m. and 9 p.m. ET Friday evening. The parents of Austin Tice, an American journalist detained in Syria for nearly a decade, are "100% certain" their son is alive.

Exclusive: Lebanon to lead hostage mediation between US and Syria, Beirut's spy chief says

The head of Lebanon's main intelligence agency has held talks with senior US officials in Washington to discuss resuming negotiations with Syria on the release of American hostages, including Austin Tice. Maj Gen Abbas Ibrahim, who heads Lebanon's General Directorate of General Security, was flown to Washington on a private flight organised by the US government.

Lebanese spy chief says he will visit Syria over missing US reporter

BEIRUT: Lebanon's intelligence chief has said he will visit Syria for talks with Syrian leaders about the fate of a US reporter who went missing in Syria a decade ago. Major General Abbas Ibrahim, said US officials want him to resume efforts to bring home Austin Tice and other Americans missing in Syria.

Explained: Who is Austin Tice, the American journalist who disappeared in Syria a decade ago?

The Joe Biden administration has initiated new efforts to locate missing journalist Austice Tice, who disappeared from Syria while covering the civil war in 2012. Who is Tice, and what do we know about his disappearance? Why have efforts to trace him failed so far?

#BringAustinHome campaign to feature sitewide messaging for detained journalist Austin Tice

Comment Gift Article Ahead of the grim ten-year anniversary of Austin Tice's abduction while reporting in Syria, The Washington Post Press Freedom Partnership urgently calls for his safe return with an "Ask About Austin" sitewide message on Sunday, August 14.

People are Eager to See Austin Home, Mother of Missing Journalist Says

Debra Tice on the 10-year search for her son, American journalist Austin Tice, who was taken captive in Syria

Transcript: American Hostage with Debra & Marc Tice, Parents of Austin Tice

MR. REZAIAN: Good afternoon. Welcome to Washington Post Live. My name is Jason Rezaian. I am a global opinions writer here at The Washington Post. My guests today are Debra and Marc Tice, the parents of freelance journalist Austin Tice. Austin was abducted in Syria, just south of Damascus.

Debra Tice on Austin's accomplishments before his capture

"He had great plans for himself, that was part of why he was in law school. Sometimes it's hard to remember that Austin was 31 three days before he was detained. So, all of the things that he had accomplished, he accomplished in his twenties...Usually, the twenties are sort of going to school, getting started, partying a lot, that wasn't Austin.

A message from Debra Tice, Austin's mother

"It's been 10 years since I've hugged my son." Debra Tice, mother of detained journalist Austin Tice, has been advocating for her son's safe return from Syria for a decade. Hear her message to the U.S. government to bring Austin home.

Biden to hold talks with Syria regime over captive US journalist

US President Joe Biden yesterday ordered his administration to hold direct talks with the Syrian regime to discuss the case of American journalist Austin Tice, who has been held in Syria for a decade.

NBC News' Lester Holt interviews parents of missing American Austin Tice

NBC News' Lester Holt interviews the parents of Austin Tice, the American freelance journalist and Marine veteran who went missing in Syria. Tice was detained at a checkpoint near Damascus in August 2012 and a month after a video of him apparently captured was posted. That was the last time Tice was seen.

#BringAustinHome banner spotlights Tice ahead of 10-year anniversary

Comment Gift Article On Tuesday, The Washington Post shined a spotlight on the unresolved case of abducted journalist Austin Tice, unveiling a #BringAustinHome banner on the exterior of The Post building ahead of the grim 10-year anniversary of Tice's disappearance while reporting in Syria.

Biden Calls on Syria to Help Secure Release of Journalist Austin Tice

US President Joe Biden on Wednesday called on Syria to help secure the release of American journalist Austin Tice, who was abducted a decade ago in Damascus. "We know with certainty that he has been held by the Syrian regime," Biden said in a statement.

Austin Tice's mother: Biden comments show he is 'ready to engage with Syria'

The mother of American journalist and former Marine Austin Tice said that President Biden's recent remarks on her son's detainment abroad show that the president is "ready to engage with Syria" on bringing her son back home. During an appearance on CNN's "New Day," host John Berman asked Tice's mother, Debra Tice, about her reaction...

10 years after Austin Tice's abduction in Syria, his parents still fight for him

Debra and Marc Tice wanted some joy. So they got a piñata. She baked a special birthday cake. They invited their whole large family to a celebration. But there was an absence that was impossible to ignore - the birthday boy.

Opinion | After 10 years of agony, it's time for Syria to free Austin Tice

After a decade of no progress, it was encouraging to see President Biden's confident assertion on Wednesday about our abducted colleague, journalist Austin Tice. "We know with certainty that he has been held by the Syrian regime," Mr. Biden said of Mr. Tice, who was detained and disappeared 10 years ago this weekend while covering the Syrian civil war.

Austin Tice Has Been Held Hostage Longer Than Any American Journalist Ever. His Texas Family Is Still Fighting for His Return.

Debra Tice's phone pinged at 4:30 a.m. on Monday, May 2, the 3,548th day since her son Austin had disappeared in Syria. Given the time difference between her home in southwest Houston and the Middle East, she was accustomed to receiving messages in the dead of night from sources and friends she'd gotten to know in the region.

Debra Tice: U.S. is capable of bringing American detainees home. 'My son qualifies. Let's go.'

Almost a decade after the abduction of American journalist and Marine veteran Austin Tice in Syria, his mother Debra Tice joins Andrea Mitchell to express her frustration and hopes for government action to bring her son home as the 10-year anniversary nears. Reacting to reports of negotiations between the U.S.

Exclusive: Fresh hopes journalist Austin Tice is alive 10 years after his disappearance

President Biden is not the first American leader to seek to free Mr Tice. Former president Donald Trump was enthusiastic at the thought of freeing American hostages. Former national security advisor John Bolton wrote in his memoir that he found Mr Trump's constant desire to call up Syrian president Bashar al-Assad "undesirable".

Austin Tice was taken hostage in Syria 10 years ago. Joe Biden must bring him home

Few expressions of the journalistic mission could be more essential and unflinching than Austin Tice's reporting on the Syrian civil war for McClatchy and others. Tice was one of the few journalists who left a country that enshrines press freedom in our founding document for one where the government and its enemies targeted reporters for abduction and worse.

Parents of missing journalist Austin Tice say 'we can feel progress' after 10 years

WASHINGTON - The parents of a Houston journalist who went missing in Syria a decade ago met at the White House in May with Joe Biden, the third president to hold office since their son disappeared.

Austin Tice has been missing for 10 years. President Biden, it's time to bring him home.

Ten years. An American, a veteran U.S. Marine, a man who became a foreign correspondent so that his fellow Americans would know what was happening in Syria, has been missing for 10 years. President Joe Biden knows about Austin Tice. So did President Donald Trump and President Barack Obama.

Remarks from Publisher and CEO Fred Ryan at the National Press Club marking Austin Tice's 10 years in captivity

On August 14, 2022, Washington Post Publisher & CEO Fred Ryan delivered remarks at a National Press Club reception to mark the tenth anniversary of Austin Tice's disappearance in Syria. Below is the full text of his remarks. As Austin's devoted parents Marc and Debra remind us, this year marks a grim milestone.

US 'directly engaged' with Syrian officials on Austin Tice case

The United States has "directly engaged" with Syrian officials on the detention of US journalist Austin Tice, a spokesman for the US Department of State said, as the Biden administration renewed its pledge to secure Tice's safe return to the country.

Austin Tice: Syria denies holding US journalist captive

The Syrian government on Wednesday denied holding American nationals captive, including journalist Austin Tice, who was abducted a decade ago in Damascus. It issued a statement in response to US President Joe Biden's comments last week that he knew "with certainty" that Tice "has been held by the Syrian regime".

National Press Club on Syria claim about Tice

The executive director of the National Press Club is expressing cautious optimism that a dialogue between the United States and Syria is starting to take shape over long held captive Austin Tice. (Aug. 17) © 2023 USA TODAY, a division of Gannett Satellite Information Network, LLC.

Austin Tice mediations between US and Syria 'going as they should be,' Lebanese general says

Mediations between the United States and Syria over U.S. Marine veteran and journalist Austin Tice, who last seen in Syria a decade ago, are going "as they should be," a Lebanese general said Tuesday. "Matters might be moving slowly but they are going as they should," Lebanese Maj. Gen.

US turns to Oman to mediate hostage release in Syria

Oman has stepped up its mediation efforts in hopes of releasing US hostages held in Syria through effective mediation at the request of the US, according to Intelligence Online .

NPC Calls For Release Of Journalist Austin Tice| Countercurrents

The National Press Club in Washington, DC today upped the public awareness campaign calling for the immediate release of war correspondent Austin Tice who was kidnapped on August 13, 2012, after being detained at a checkpoint near Damascus, Syria.

Top Lebanese intel chief, mediator with Syria steps down

BEIRUT (AP) - A Lebanese intelligence chief who has mediated the release of Westerners held in Syria and also acted as a mediator within Lebanon stepped down Wednesday after attempts to extend his term failed. Maj. Gen. Abbas Ibrahim's term as a head of the General Security Directorate ends Thursday, when he reaches retirement age of 64 in Lebanon.

A somber WHCD affair

Welcome to POLITICO's West Wing Playbook, your guide to the people and power centers in the Biden administration. With help from Allie Bice. Send tips | Subscribe here | Email Eli | Email Lauren Unlike most of the people headed Saturday to the Washington Hilton ballroom, DEBRA TICE would give everything in the world to not attend the White House Correspondents' Dinner.

Austin Tice's mother says assurances about efforts to bring him home have "lost their strength"

During his speech at the White House Correspondents' Dinner Saturday, President Biden brought up American journalist Austin Tice who was kidnapped in 2012 while reporting in Syria. Tice's mother, Debra Tice, discusses the U.S. government's efforts to bring her son home on CBS News.

Conversation with Debra Tice, Mother of Austin Tice, Polk Award-winning Journalist Held in Syria Since 2012

Conversation with Debra Tice, Mother of Austin Tice, Polk Award-winning Journalist Held in Syria Since 2012 Where: National Press Club, 529 14 th Street NW Washington, DC 20045 13 th floor, Zenger Room The National Press Club is hosting a news conference with Debra Tice , mother of award-winning journalist Austin Tice who has been held in Syria since 2012.

WSJ News Exclusive | U.S. Revives Talks With Syria Over Missing Journalist Austin Tice

DUBAI-The Biden administration has renewed direct talks with Syria to determine the fate of missing journalist Austin Tice and other Americans who disappeared during the nation's civil war, according to Middle East officials familiar with the efforts. U.S.

Russian release fuels hopes for Biden action on US captives held worldwide

ate last month saw the release of Trevor Reed, a US citizen and former marine who had been detained in Russia since 2019 on a nine-year sentence for endangering the "life and health" of Russian police officers.

Austin Tice's parents tell CNN they received support from Biden for efforts to get him home | CNN Politics

The parents of Austin Tice, an American journalist kidnapped in Syria nearly a decade ago, told CNN they received support from President Joe Biden on efforts to bring their son home.

April 13, 2022

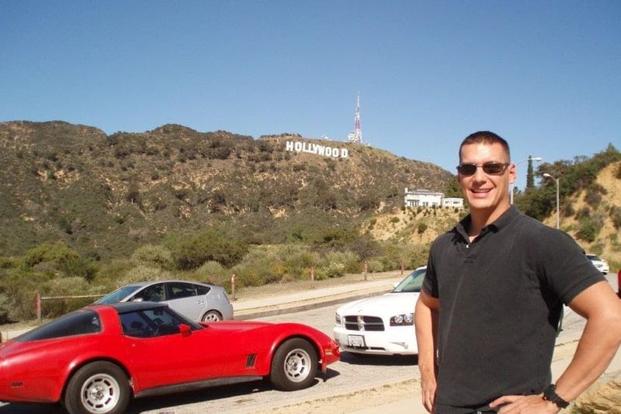

BAKER PRIZE FOR EXCELLENCE IN LEADERSHIP: AUSTIN BENNETT TICE

Baker Prize for Excellence in Leadership: Austin Bennett Tice

Apr. 13, 2022In May 2012, while a student at Georgetown Law School, Austin Tice traveled to Syria as a freelance journalist to report on the country’s ongoin…

Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy honors Austin Tice for his courage and service in reporting on Syria’s violent and tragic civil war. His outstanding work exemplifies the values of the James A. Baker III Prize for Excellence in Leadership. This event marks the eighth time the award has been conferred in the Baker Institute’s 28-year history.

Parents of hostage Austin Tice, who was abducted in Syria in 2012, meet with Biden

President Biden is meeting Monday with the parents of Austin Tice, the freelance journalist and veteran who was abducted in Syria a decade ago, after saying Saturday at the White House Correspondents Dinner that he'd like to meet them and talk about their son.

Austin Tice's family says the U.S. government is their biggest obstacle in bringing their son home | Houston Public Media

The family of Houston journalist Austin Tice, who reportedly has been in Syrian custody since 2012, say they're facing new obstacles in seeking his return - specifically, the U.S. State Department. Houston native Austin Tice was working as a freelance journalist reporting on the Syrian conflict when he was abducted in 2012 .

Mother of US journalist detained in Syria seeks Qatar's help

Analysts believe the Gulf state's possible role in securing the release of the journalist can be a challenge, given its staunch refusal to normalise with the Bashar Al Assad regime. The mother of American journalist, Austin Tice, who has been held hostage in Syria since 2012, hopes that Qatar's Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani discusses her son's release during Monday's meeting with President Joe Biden in Washington.

Mother of abducted U.S. journalist Austin Tice to meet with national security adviser Jake Sullivan

The mother of abducted American journalist Austin Tice is meeting with national security adviser Jake Sullivan Friday, a person familiar with the meeting told CBS News. Debra Tice claims President Biden has so far been unwilling to meet with her. Austin Tice, now 40, was abducted in Syria in 2012.

Austin Tice's mother says White House a 'hurdle' to his return

The mother of Austin Tice, a freelance journalist taken captive in Syria nine years ago, said the White House remains a "hurdle" to bringing her son home. Tice, a former Marine captain from Texas who served in Afghanistan and Iraq, is among roughly half a dozen US citizens thought to have been seized by the Syrian government or allied forces.

White House is a 'hurdle' to son Austin Tice's release, mother says

The mother of abducted journalist Austin Tice said Thursday that the White House has become a "hurdle" to freeing her son from captivity, suggesting that his release was not a priority for the highest levels of the Biden administration.

Petition to free Austin Tice gains momentum following 5K run - Editor and Publisher

A petition to free Austin Tice, an award-winning journalist and Marine veteran being detained unjustly in Syria, has gained momentum thanks in part to last weekend's virtual 5K event sponsored by the National Press Club. The Club's petition for Tice on Change.org had garnered approximately 142,000 signatures on Nov. 7.

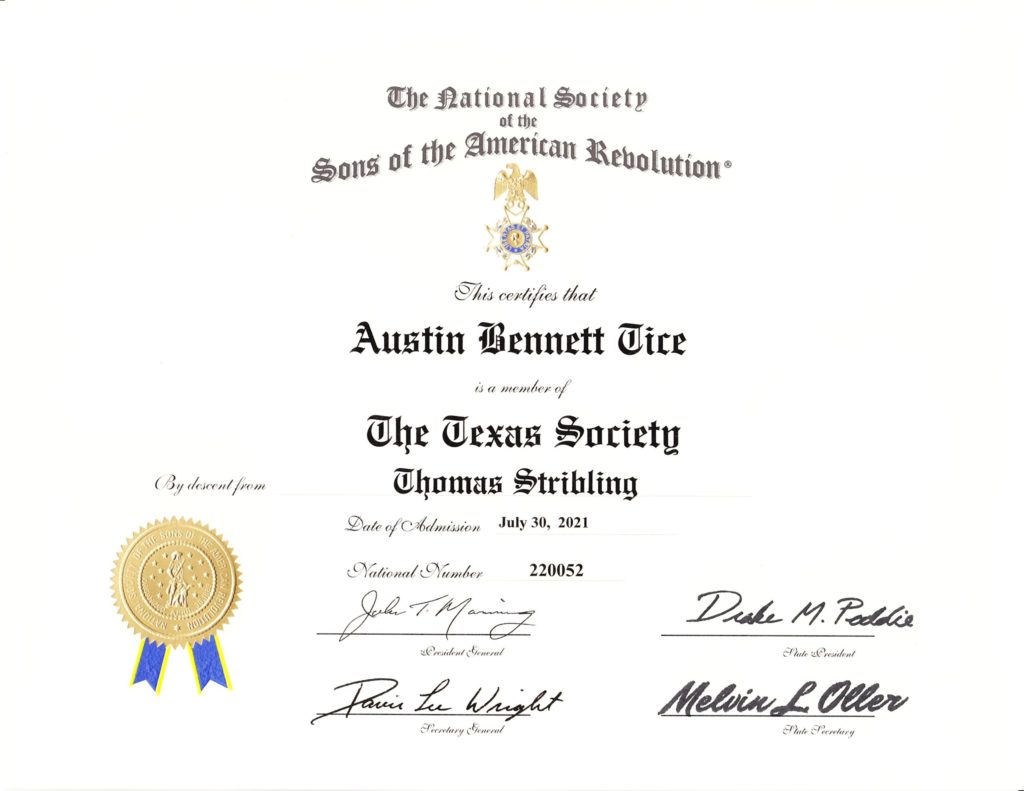

October 18, 2021 - Austin is inducted into the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution

October 14, 2021 by Abby Tucker

Parents of Austin Tice Call on Biden Administration To Prioritize Tice’s Release

The parents of Austin Tice (SFS ’02) wrote an open letter to President Joe Biden on Oct. 3, calling on his administration to prioritize Tice’s safe return to the United States.

Tice, who has been missing since August 2012, was kidnapped while covering the Syrian civil war, the summer after completing his second year at Georgetown University Law Center. Over a month after his disappearance in Darayya, a video published anonymously showed Tice blindfolded and surrounded by armed and masked men. While the Biden administration believes Tice is alive, no presidential administration has been able to bring him home.

Georgetown University | Debra and Marc Tice urge Biden to put all efforts towards securing Tice’s return in the letter, which comes nine years after his disappearance.

Debra and Marc Tice, Tice’s parents, published their open letter in The Washington Post on Oct. 3, specifically calling on Biden to engage diplomats and other U.S. State Department officials in an effort to help secure Tice’s release and return to the United States.

The Biden administration should prioritize Tice’s release because it has emphasized family protections and values, according to the Tices’ letter.

“In these early days of your administration, you have clearly messaged that family is at the core of your agenda,” the letter reads. “We believe that if Austin were a member of your family, all the Bidens would rally around and come together to bring him home. On Austin’s behalf, because you are president of the country he honorably served as a Marine Corps officer, we are asking you for that kind of all-in effort.”

The Tice family hopes that continued activism will ultimately help secure Austin Tice’s safe return to the United States, according to Debra Tice.

“We continue to relentlessly advocate for Austin’s secure release and safe return. We hope and pray he will soon walk free,” Tice wrote in an email to The Hoya.

Georgetown continues to support the Tice family’s calls for action from the Biden administration, according to Joel Hellman, dean of the School of Foreign Service.

“We at SFS stand with the Tice family in urging the U.S. Government to do everything within its power to bring Austin home,” Hellman wrote in an email to The Hoya. “His commitment to risk everything in order to expose the suffering of the Syrian people represents the true spirit of Georgetown.”

The Georgetown community has remained active in calling for Tice’s release. Georgetown community members sent letters to congressional representatives in April 2021, urging their representatives to call on the Biden administration to prioritize Tice’s return.

Tice is also important to journalists around the world, according to Doyle McManus, director of Georgetown’s journalism department.

“Austin Tice is important to the journalistic community, Austin Tice is important to the Georgetown community, and Austin Tice, at the end of the day, is important to all of us,” McManus said in a phone interview with The Hoya. “He was a journalist carrying out the search for truth, and it’s vitally important that the U.S. government do what it can to protect people who do that, or fewer and fewer people will ever be able to do that again.”

Despite activism for Tice’s return, Tice’s parents have expressed frustration over a lack of action taken to secure his release, according to a statement released Aug. 11, Tice’s 40th birthday.

The U.S. government continues to commit resources to helping secure Tice’s release from Syria, according to a U.S. official.

CLIPS

POLITICO National Security Daily: TICE FAMILY URGES BIDEN ACTION— The parents of AUSTIN TICE, the journalist and former Marine detained in Syria, penned an open letter to the White House today, demanding the president make Tice’s return a higher priority for the administration. “Our entire family urges you to prioritize Austin’s secure release and safe return to us and to the country he loves,” Debra and Marc Tice wrote. “Mr. President, Austin needs you to step out and boldly lead. Please say our son’s name in public. Talk about Austin Tice; let people in Washington and Damascus know you are thinking of him. Put courage in their hearts to do the right thing. We have no doubt your family will support you, and our government will unite behind you.” The Tices also requested a meeting between their family and Biden’s to talk about Austin and “send a strong message across our country and overseas.” Tice has been held hostage in Syria for nine years, and efforts by U.S. officials to bring him home so far haven’t worked. A National Security Council spokesperson responded to the letter after a NatSec Daily query: “We continue to emphasize that Austin’s release and return home are long overdue. The Biden administration continues to call on Syria to help release Austin Tice and every American unjustly detained in Syria. We are committed to following all avenues, including engagement with anyone who can help with Austin’s release and return home.” “We have been and remain open to direct communication with anyone who can help us bring Austin and other American hostages home,” the spokesperson added.

POLITICO Playbook PM: CALL TO ACTION — DEBRA and MARC TICE, the parents of AUSTIN TICE, are out with an open letter to Biden urging him to take action in securing Austin’s return from captivity in Syria. “Mr. President, Austin needs you to step out and boldly lead. Please say our son’s name in public. Talk about Austin Tice; let people in Washington and Damascus know you are thinking of him. Put courage in their hearts to do the right thing. We have no doubt your family will support you, and our government will unite behind you.” Debra and Marc also requested a meeting with Biden and his family to “show that you have taken the lead and we are working on this together.” The letter (includes link to Press Freedom Partnership newsletter)

The Hill: Family of Austin Tice calls on Biden to help secure son’s release from Syria— The family of Austin Tice, the American journalist and former Marine who has been held captive in Syria for nearly nine years, is calling on President Biden to prioritize securing their son’s safe release…“We believe that if Austin were a member of your family, all the Bidens would rally around and come together to bring him home,” the Tice family wrote in a letter obtained by The Washington Post…The Hill reached out to the White House for comment.

CNN’s Reliable Sources: Austin Tice’s parents ask for meeting with Biden — Oliver Darcy writes: “Austin Tice’s parents say they would ‘welcome the opportunity’ to meet with President Biden and his family. In an open letter that will run as a full-page ad in the Washington Post on Monday, Debra and Marc Tice write, ‘We’d like to tell you more about Austin. A meeting of our loving families would send a strong message across our country and overseas.’ The letter comes nine years after Tice was abducted. The Tice family told Biden that they believe ‘if Austin were a member of your family, all the Bidens would rally around and come together to bring him home.’ They are calling on him to engage on ‘that kind of all-in effort’ for their son…”

Military Times Early Bird Brief: An open letter to President Biden for Austin Tice (links to Press Freedom Partnership newsletter)

Lawfare: Today’s Headlines and Commentary— The family of Austin Tice, the American journalist and former Marine detained in Syria, penned an open letter to Biden requesting the president directly orders to facilitate Tice’s return, reports the Hill. The letter contends that current officials must “build off the breakthroughs that were achieved by the previous administration” through direct engagement and relevant dialogue.

The Poynter Report— The Washington Post Press Freedom Partnership’s October newsletter features an open letter to President Joe Biden from the parents of Austin Tice, the freelance journalist who was abducted in Syria in 2012 and is believed to still be alive.

Editor & Publisher: An open letter to President Biden from the parents of Austin Tice (includes link to letter on WashPostPR blog)

TWEETS

The Hill @thehill: Family of Austin Tice calls on Biden to help secure son’s release from Syria

Fox News Foreign Correspondent Benjamin Hall @BenjaminHallFNC: Austin Tice, journalist and marine has been imprisoned in Syria for 9 years. His parents wrote an open letter to President Biden. “We believe that if Austin were a member of your family all the Bidens would rally around and come together to bring him home”

CNN Senior Media Reporter @OliverDarcy: Austin Tice’s parents write open letter to Biden: “We believe that if Austin were a member of your family, all the Bidens would rally around and come together to bring him home. On Austin’s behalf … we are asking you for that kind of all-in effort.”

Reuters Nat Sec Correspondent @JonathanLanday: “President Biden, speaking for Austin, our entire family urges you to prioritize Austin’s secure release and safe return to us and to the country he loves.” #freeaustintice

Barstool Sports ‘Zero Blog Thirty’ Podcast (military podcast) Co-Host Kate Mannion @katebarstool (111k followers): #FreeAustinTice

Journalist Lauren Wolfe @Wolfe321 (86.4k followers): Austin Tice’s parents are running an ad in WaPo, 9 yrs after he was abducted in Syria while reporting. “Plse say our son’s name in public. Talk about Austin Tice; let people in Washington & Damascus know you are thinking of him. Put courage in their hearts to do the right thing.”

White House Correspondents Association @WHCA: Moving and powerful letter from the parents of journalist Austin Tice, now held in captivity for 9 years.

Former NPR Host and Executive Producer Kitty Eisele @RadioKitty: And please don’t forget missing journalist #austintice, held in Syria for nine years now.

Council on Foreign Relations Fellow Bruce Hoffman @hoffman_bruce: After 9 years Austin Tice remains imprisoned in Syria.

Society of Professional Journalists @spjtweets: “President Biden, you speak often and movingly of the significance of journalism and its value in a democratic society. Austin obviously shares these values with you and is paying a high price for doing this critically important work.” #FreeAustinTice wapo.st/3DcghsQ

Military Times Reporter Todd South @tsouthjourno: U.S. citizen and Marine veteran Austin Tice was abducted more than nine years ago in Syria. His family pleads for President Joe Biden to bring him home: s2.washingtonpost.com/camp-rw/

An open letter to President Biden from the parents of Austin Tice

The following letter appears in The Washington Post Press Freedom Partnership's October newsletter : Dear Mr. President, August 14 is the date of our son's abduction; this year it marks nine years of detention in Syria. President Biden, speaking for Austin, our entire family urges you to prioritize Austin's secure release and safe return to us and to the country he loves.

U.S. government offers reward of up to $1 million for safe return of Austin Tice - Editor and Publisher

The United States government is offering a reward of up to $1 million for information leading directly to the safe location, recovery and return of Austin Bennett Tice, a freelance journalist and photographer who was kidnapped in Damascus, Syria, on Aug. 13, 2012. Click here to read more.

Biden administration calls on Syria to return missing journalist Austin Tice

The Biden administration Wednesday called on Syria to help return Austin Tice, a freelance journalist who disappeared in the war-torn country nine years ago and is believed to be held by the regime. "We believe that it is within Bashar al-Assad's power to free Austin," Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in a statement marking Tice's 40th birthday.

Parents of Austin Tice, journalist who disappeared in Syria, speak out on his 40th birthday

Austin Tice, a freelance journalist and former Marine, disappeared nine years ago while on assignment in Syria. Debra and Marc Tice, who have never given up hope for their son's safe return, spoke to Lester Holt in an exclusive interview on their son's 40th birthday.

Opinion: Austin Tice is turning 40. Can this president finally bring him home?

A banner at the Newseum raises awareness about Austin Tice, a journalist who is being held hostage. (Kery Murakami/Kery Murakami/ Express)

It was the last birthday Austin Tice celebrated as a free man.

Three days later, on Aug. 14, 2012, Tice — a young freelance journalist who had traveled to Syria to document that country’s ongoing conflict, including for The Post — was abducted at a roadside checkpoint on his way to Damascus. Video and information released since suggests that he is alive and being held captive by an armed group allied with the Syrian government.

The United States should never stand by when dictatorships take our citizens hostage. But the offense is especially outrageous when the victims are journalists, who provide the information and perspective our democracy needs to function, often at great personal risk.

The offense is especially heartbreaking when the victim is a person like Austin, who has always embraced the ethos of service to others that distinguishes our finest citizens. He was an Eagle Scout who, during his decade as an infantryman in the Marine Corps, deployed twice to Iraq and once to Afghanistan, rising to the rank of captain before leaving for the reserves. He went on to study at Georgetown Law; during his final summer there, a time when many students pursue lucrative law-firm positions, Tice followed a different path. He wanted to use his unique skills and experiences to tell the world the devastating stories of a country riven by civil war. His courageous, groundbreaking journalism from Syria was honored with the prestigious George Polk Award.

Those who know and love Austin have done everything possible to secure his release. The past nine years have been especially agonizing for Austin’s parents, Marc and Debra Tice. They surely imagined in 2012 that, by Austin’s 40th birthday, he would have begun his law practice, married, started a family and continued serving the country he loves. The idea that he would have spent this entire time languishing at the hands of brutal captors in Syria would have filled them with horror — as it should all of us.

Our country should not — cannot — leave Austin Tice behind. Unfortunately, his plight has now extended into a third presidential administration. Obama was not able to free him. Trump was reportedly determined to bring Austin and other hostages home but was thwarted by obstacles that included his own bureaucracy.

Today, President Biden has an opening to succeed where his predecessors failed. From Syria’s point of view, a new negotiating partner can offer a fresh start. A new administration still in search of a Syria policy has a chance to place Tice’s return front and center.

In this particular case, it also involves weighing everything the United States wants out of Syria — an end to the devastating conflict, heinous human rights abuses, war crimes and oppression — alongside the prolonged suffering of Tice and his family. Each day that Tice remains detained, he and his family are joined in their suffering by the American people, who expect that our citizens captured abroad will not be abandoned to their fate and that our leaders will stand up for democratic values and a free press.

As the father of another young man who served his country with distinction, Biden can surely understand that whatever diplomatic challenges he faces pale against the unspeakable pain Tice’s parents have endured day after day, hoping against hope that our government can bring their beloved son home.

Turning 40 is a milestone in anyone’s life. In Austin Tice’s case, as he enters his 10th year of imprisonment, it means he has spent nearly a quarter of his life held hostage. It is now up to Biden to ensure that, before Austin’s next birthday, his family’s hopes of his safe return are fulfilled.

Help bring attention to the case of detained American journalist Austin Tice by wearing a #FreeAustinTice bracelet from The Washington Post Press Freedom Partnership, available for free in The Post store.

As Austin Tice spends his 40th birthday in captivity, RSF reaffirms its commitment to his safe return

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) calls for the safe release and return of American journalist Austin Tice, who was kidnapped near the Syrian capital of Damascus on August 14, 2012 while reporting on the country’s civil war. Austin, who will turn 40 on August 11, is entering his tenth year in captivity.

“Austin should be marking the milestone of his 40th birthday surrounded by loved ones and celebrating the many personal and professional successes that he would have no doubt had if he hadn’t been held against his will these past nine years,” said Anna K. Nelson, the Executive Director of RSF USA. “It’s high time that Austin be allowed to come home. His parents, Debra and Marc, have worked tirelessly to end his ordeal. We’re asking the US government to continue relevant and direct engagement with the Syrian government regarding Austin’s case, and for those who are detaining him to do the right thing in letting Austin go.”

March 2021 marked the tenth anniversary of the popular uprising that led to Syria’s civil war, which has had a devastating impact on the country’s media and journalists. According to information gathered by RSF and its partners since 2011, at least 300 professional and non-professional journalists have been killed while covering artillery bombardments and airstrikes, murdered by various parties to the conflict, or have either disappeared or fled abroad.

“Journalists in Syria have been under attack for a decade,” said RSF Secretary-General Christophe Deloire. “Nine years in captivity is nine too many for Austin and his family — RSF stands firm in its resolve that Austin be released and allowed to return to the US as soon as possible.”

RSF has been a steadfast advocate of Austin Tice for many years, leading public advocacy campaigns to ensure his return home remains a top priority for the US federal government. Previously, RSF partnered with The National Press Club and other press freedom organizations to launch the “Night Out for Austin Tice,” an initiative to raise awareness and funds to supplement the $1 million FBI reward for information leading to Austin’s safe return. In 2016, RSF partnered with The Washington Post, The New York Times, USA Today, McClatchy and other media outlets to launch the #FreeAustinTice campaign. Print and digital ads promoting the campaign were run in outlets to raise awareness of Austin Tice’s case across the country.

The United States ranks 44th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2021 World Press Freedom Index and Syria ranks 173rd.

‘We Won’t Give Up’: Advocates Hope Biden Will Finally Bring Marine Vet Austin Tice Home

It’s been more than eight years since Marine Corps veteran and freelance journalist Austin Tice was detained at a checkpoint outside of Damascus as he worked to cover the Syrian war’s impact on civilians. He hasn’t been seen since, but those who know him believe that he is still alive.

U.S. officials told McClatchy news service April 14 that they are operating “with the sincere belief” that Tice is alive, and 80 lawmakers signed an April 26 letter urging the Biden administration to use “every constructive tool in [its] power to secure Austin’s safe return.”

Tice is one of about six U.S. citizens believed to be held by the Syrian government or forces allied to it. His case is particularly complicated because no group has claimed responsibility for his capture.

There have been several unsuccessful attempts to get Austin back, including an August 2020 trip in which Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs Roger Carstens and then-Senior Director for Counterterrorism at the National Security Council Kash Patel met with the head of Syria’s intelligence agency, Ali Mamlouk.

Syria is ranked 173 out of the 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders 2021 World Press Freedom Index; at least 300 journalists have been arrested and almost 100 have been victims of abduction in the country since 2011.

Several of the lawmakers who signed the April 26 letter to Biden are veterans, including Rep. Van Taylor, R-Texas, and Rep. Seth Moulton, D-Mass.

“I certainly feel a sense of camaraderie with him, not just as a fellow American but as a fellow Marine,” Moulton, a member of the House Armed Services Committee who served in the Marine Corps from 2002 to 2008, told Miiltary.com. “I had the honor of meeting with Debra and Marc Tice, Austin’s parents, back in 2019. And I promised them that our government would not give up the fight to bring him home. And that still holds true today. We won’t give up.

“It is our duty to do everything we can to bring him home. … Austin has spent every birthday, every holiday alone and imprisoned in Syria thousands of miles away from family, friends and the country he so bravely served,” he added. “We’re encouraged by reports from the Biden administration that Austin may still be alive. It’s imperative that the administration use every resource at its disposal to bring him home to his family and friends. They don’t want to spend another holiday without him.”

Taylor, who served on active duty in the Marine Corps for 10 years, including in combat during Operation Iraqi Freedom, said, “Congress is prepared to do anything in its power” to bring Austin back home, adding that he was proud that members “of all political stripes all over the country” came together to urge Biden to act.

“As a veteran, I think we need to bring everybody home, especially our veterans,” Taylor, who left the Marine Corps Reserve as a major, told Military.com. “I want to see the Biden administration apply pressure on the Assad regime to get Austin Tice home.”

Retired Lt. Col. Brian Bruggeman, who served in the Marine Corps for 23 years, worked with Tice for about nine months.

He described Tice as “challenging in a good way,” adding that he always asked thought-provoking questions.

“Austin’s questions were not limited to the tactical situation that we were in. … They were about our role in Afghanistan at the time or … how to best help the Afghan people,” Bruggeman told Military.com. “He developed an affection for the people that lived in the country in which we were operating. … Austin’s affection was just fundamental to who he was.”

Bruggeman lost a close friend and fellow pilot in a training accident in early 2012. Though Tice was no longer with the unit, he reached out to Bruggeman. “And he said, ‘Hey, I understand if you didn’t want to do this, but let me know if you want to talk to my mom, she’s really good at talking about this stuff.’ And I’ll never forget that.”

Col. Masahiro Oda, who currently serves in the Japanese Army, met Tice in 2010 at the U.S. Army’s Airborne Basic Training at Fort Benning, Georgia. He described Tice as “a very gentle and a very kind person.”

“I felt his strong sense of justice, and I felt that he has a very strong heart,” Oda said as he placed his hand over his own heart. “I think that he went to the Middle East based on his sense of justice. I believe that he is working hard somewhere in the Middle East. I want to believe.”

Bruggeman is also hopeful that he will see Tice again.

“I’m proud to have gotten to know [him]. I’m proud to be part of the effort in some small way to keep his story alive,” he said. “I look forward to seeing Austin again; that’s about it.”

More than anything, Bruggeman said he would like to know that the government “is doing everything they can to find, locate and get Austin Tice back.”

“I understand we cannot invade any country we want [in order] to pick any person up unless we know exactly what that person is. But, short of that, we can do everything we can to find where that person is and get them out through any means possible,” he said. “Just knowing that the people in our government are pursuing that with passion, that’s what I want.”

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated to correct the titles of Roger Carstens and Kash Patel.

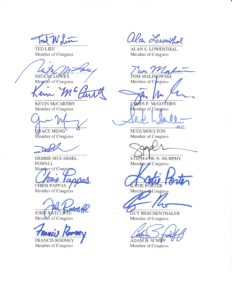

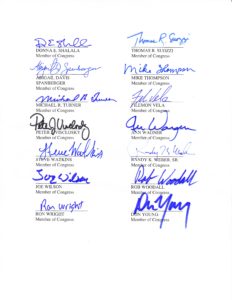

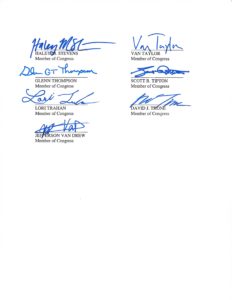

Monday, April 26, 2021, President Biden received a letter signed by a bi-partisan group of 80 US House Representatives and Senators, expressing their support for the use of every diplomatic means to secure Austin’s safe return home. We are deeply grateful to the wonderful team who conceived and delivered this initiative, to the 2000+ friends who sent their federal reps a letter, and to the Senators and Representatives who responded and expressed their firm support. Click the images to enlarge.

Trump wants to see Austin Tice home before he leaves office, says national security adviser

Mom of missing American Austin Tice claims ‘insubordinate’ US officials holding up release talks

February 28, 2020

The mother of Austin Tice, an American journalist believed imprisoned by militants in Syria since 2012, told “Tucker Carlson Tonight” Friday that the Trump administration should do whatever it takes to bring her son home.

Host Tucker Carlson said that the Syrian government invited the U.S. government to send a representative to Damascus to discuss Tice’s case, but according to the host, “neocons at the State Department have intervened and, therefore, it hasn’t happened.”

Debra Tice told Carlson that officials who are opposed to opening negotiations are “insubordinate to the president of the United States because it’s his will for Austin to walk free and the only way that he’s going to do that is to have a dialogue and the Syrians have opened the door.”

Tice added that Trump assured her verbally and in writing that her son will come home and said she trusts the president to do so.

“It’s on us to respond [to the Syrian government] and engage in a conversation that will secure Austin’s safe release,” Debra Tice said.

“The question is who is going to stand in the way of the President of the United States bringing our son home?” Debra Tice said. “And who would want to do that?”

Trump asks Syria to Free Austin Tice Immediately

BY FRANCESCA CHAMBERS

MARCH 19, 2020 01:43 PM

President Donald Trump on Thursday called on Syria to release freelance journalist Austin Tice, who worked for McClatchy and other news organizations and has been missing since 2012.

“We hope the Syrian government will do that. We are counting on them to do that. We’ve written a letter just recently,” Trump said at the start of a press briefing on the coronavirus pandemic.

“He’s been there for a long time. And he was captured long ago. Austin Tice’s mother is probably watching, and she’s a great lady. And we’re doing the best we can,” he said.

Tice was reporting on the war in Syria when he went missing in 2012. His parents have been relentless in asking the U.S. government to help bring him home.

“I want to let everyone know that recovering Americans held captive and imprisoned abroad continues to be a top priority for my administration,” Trump said.

He said his administration has been “working very hard with Syria to get him out” and praised Robert O’Brien, who was previously a chief hostage negotiator and is now the national security advisor, for his work.

“So Syria, please work with us. And we would appreciate you letting him out. If you think about what we’ve done, we’ve gotten rid of the ISIS caliphate for Syria. We’ve done a lot for Syria,” Trump said.

“We have to see if they’re going to do this. So it would be very much appreciated if they would let Austin Tice out immediately,” he said.

Tice has been missing since August 2012. The United States government is offering a $1 million reward for information that leads directly to his return.

“This administration is pressing it much more diligently than the previous administration,” Debra Tice told McClatchy in a January interview. “There is a deliberate, concerted effort to make this happen.”

In a statement after the president’s remarks on Thursday, she said the Tice family is grateful to O’Brien and Trump for their advocacy of her son’s release. “The President has our deepest appreciation,” Tice wrote.

“At this very disturbing time for our nation and the world, it is more important than ever to get Austin safely home. As President Trump said, we ask the Syrian government to do all they can to locate and safely return Austin to our family. May it be soon!” she said.

FRANCESCA CHAMBERS

Francesca Chambers has covered the White House for more than five years across two presidencies. In 2016, she was embedded with the campaigns of Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders. She is a Kansas City native and a graduate of the William Allen White School of Journalism and Mass Communications at the University of Kansas.

Mother of detained reporter urges U.S. to talk with Syrians

A single U.S. government official is believed to be blocking talks with Syrian authorities about securing the release of an American journalist said to be held in that country, the reporter’s mother told a press conference Monday, January 27th at the National Press Club.

Friday, September 27, 2019, President Trump received a letter signed by a bi-partisan group of 121 US House Representatives and 52 Senators, expressing their support for the use of every diplomatic means to secure Austin’s safe return home. Our deepest thanks to the over 100 volunteers who visited every Congressional office on Austin’s behalf, and to all the Senators and Representatives who expressed their firm support. Click the images to enlarge.

It’s been seven years. Let Austin Tice go.

August 8 at 5:05 PM

THE WAR in Syria is winding down, at least around Damascus, where journalist Austin Tice was kidnapped seven years ago by unknown abductors. Our determination to see him free is not winding down. He has lost seven years of freedom that cannot be replaced, but release would give him a chance to enjoy the precious years he has remaining. Whatever motives the kidnappers had in 2012 must have long dissipated. We appeal to them to bring this long nightmare to a close and set him free.

Mr. Tice, a former Marine captain, felt a calling to report on the war in Syria and followed his curiosity there. Some of his work appeared in The Post, and he was also published by McClatchy newspapers. Planning to leave Syria for Lebanon on Aug. 14, 2012, having just turned 31 years old, he got into a taxi in Darayya but never made it to the border. Five weeks later, a video emerged that showed him being held by a group of unidentified armed men. The title of the video was “Austin Tice is Alive.”

His parents, Debra and Marc Tice, said in a recent open letter, “Austin is alive, with the hope of once again walking free.” A $1 million reward offered by the FBI, which has since been matched by a coalition of media organizations, has prompted several new sources of information to come forward, his father said in December, without specifying the new information. The family has said there were no claims of responsibility or messages from the captors since the initial video. Recently, an American traveler, Sam Goodwin, who was detained by government forces in Syria, was released after nearly two months following mediation by a Lebanese general. While the details of the mediation are not known, the release should be taken as a sign of what is possible.

We can only guess what horrors Mr. Tice has been through. Terry Anderson, the Associated Press reporter who was kidnapped by Hezbollah in Beirut in March 1985, recalled in his memoir the mental stress of solitary confinement. “There is nothing to hold on to, no way to anchor my mind. I try praying, every day, sometimes for hours. But there’s nothing there, just a blankness. I’m talking to myself, not God.” But Mr. Anderson, also a Marine veteran, held tenaciously to the hope of release and eventually found support from other captives. Mr. Anderson was held longer than any other hostage of the Lebanon war, released in 1991 after 2,455 days in captivity.

Mr. Tice has now been held longer than Mr. Anderson. This is a grim benchmark for Mr. Tice and for his family. But Mr. Anderson’s story shows that human willpower can be an indomitable force against the most difficult odds. We hope Mr. Tice has also found such strength, and that those who seized him seven years ago will at last open the cell door and let him go.

![]()

Austin Tice Has Been Held Captive for Nearly 7 Years. He Must Be Freed.

This law student and freelance journalist was seized in Syria in 2012.

The editorial board represents the opinions of the board, its editor and the publisher. It is separate from the newsroom and the Op-Ed section.

Aug. 8, 2019

Two anniversaries approach for Austin Tice, an American freelance journalist. On Sunday, he will turn 38; three days later, he will start his eighth year in captivity, probably somewhere in Syria.

Mr. Tice is a graduate of the Georgetown School of Foreign Service, served as a Marine officer and was enrolled at Georgetown Law. But he longed to be a reporter, so in May of 2012, with a year to go in law school, he set out for Syria to report on how the civil war was affecting the lives of ordinary people.

The war was just entering its second year, and there wasn’t much reporting about it — getting into combat zones from either the government side or the rebel side was dangerous and difficult. So Mr. Tice went in illegally. Soon his images, interviews and reports were appearing in The Washington Post, McClatchy newspapers, Agence France-Presse and other news outlets.

Mr. Tice intended to leave after his 31st birthday, on Aug. 11, after filing his last pieces. On Aug. 14 he left for Lebanon by car from the Damascus suburb of Darayya, then in rebel hands. Shortly after, he was detained at a checkpoint.

Five weeks later, a 47-second video titled “Austin Tice Still Alive” was posted on a pro-government web page, in which Mr. Tice is being hustled along a rocky mountainside by what is meant to appear to be a group of Islamist militants. They force Mr. Tice to recite, in clumsy Arabic, a prayer Muslims say before dying, after which, breathless and distraught, he says in English: “Oh, Jesus. Oh, Jesus.” There were doubts at the time about the authenticity of the video, in part because the captors did not behave as militants usually do.

Without offering any evidence, other pro-regime news sources subsequently posted messages describing Mr. Tice as an Israeli agent or accusing him of killing three Syrian officers. But there has been no contact with his captors.

Mr. Tice’s parents, Marc and Debra Tice, are convinced he is alive and have worked tirelessly for his release, traveling several times to Lebanon, putting pressure on every diplomat and official they can, organizing special events to keep his fate in the public eye. The State Department has said it is operating on the presumption that Mr. Tice is alive, and it has been working through the Czech Embassy in Damascus (the United States Embassy is closed) to press the Syrian government for information. The F.B.I. has offered a $1 million reward for information leading to his return, and journalism organizations such as Reporters Without Borders and the National Press Club have joined in campaigning for Mr. Tice’s freedom.

Mr. Tice was not a combatant. He was a journalist who went to Syria to report on the plight of people in a terrible civil war. That he was a freelance contributor makes no difference — his self-assigned mission was the same as that of all journalists who confront the enormous dangers of conflict, hostile governments and rapacious bandits to let the world know what is really happening. According to Reporters Without Borders, 239 journalists and 17 of their assistants are currently known to be imprisoned for their work.

Mr. Tice has already paid heavily for his honorable efforts. Demands for his release must not cease until he is free.

Houston restaurants will raise funds for a kidnapped journalist

Houston restaurants will raise funds for a kidnapped journalist

April 17, 2019 – On May 2, Chris Shepherd’s Georgia James, One Fifth Mediterranean, and UB Preserv will participate in a national fundraiser for Austin Tice, a Houston-born journalist who has been held captive in Syria since 2012. According to Houstonia, the event organized by the National Press Club involves more than 50 restaurants across the Untied States and beyond, all of which will donate a portion of proceeds to a fund that will be added to the $1 million reward offered by the Federal Bureau of Investigation for “information leading to Tice’s safe return to the U.S.”

The Big Picture with Olivier Knox, SiriusXM – P.O.T.U.S, February 12, 2019

We thank Congressman Al Green and his co-sponsors Representative Henry Cuellar, Representative Vincente Gonzalez, Representative Sheila Jackson Lee, Representative Adam B. Schiff, Representative Ruben Gallego and Representative Bobby L. Rush for introducing this Resolution in the first session of the 116th Congress. We encourage others to express their thanks to them as well!

1ST SESSION H. RES. 17

Expressing concern over the detention of Austin Tice, and for other purposes.

IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

JANUARY 3, 2019

Mr. GREEN of Texas submitted the following resolution; which was referred

to the Committee on Foreign Affairs, and in addition to the Permanent

Select Committee on Intelligence (Permanent Select), for a period to be

subsequently determined by the Speaker, in each case for consideration

of such provisions as fall within the jurisdiction of the committee concerned

RESOLUTION

Expressing concern over the detention of Austin Tice, and

for other purposes.

Whereas Austin Tice is a 37-year-old veteran, having served

in the Marine Corps as an infantry officer, a Georgetown

law student, and a graduate of Georgetown University,

from Houston, Texas;

Whereas Austin is an Eagle Scout, National Merit Scholarship finalist, and eldest of seven children;

Whereas Austin was a contributing freelance journalist to

McClatchy Newspapers, the Washington Post and other

media outlets and a recipient of the 2012 George Polk

Award for War Reporting;

Whereas, in May 2012, Austin crossed the Turkey-Syria border to report on the intensifying conflict in Syria;

Whereas, on August 11, 2012, Austin celebrated his 31st

birthday in Darayaa, Syria;

Whereas, on August 14, 2012, Austin departed for Beirut,

Lebanon, was detained at a checkpoint near Damascus,

Syria, and contact with family, friends, and colleagues

ceased;

Whereas, in late September 2012, a video clip appeared on

YouTube showing Austin blindfolded and being prodded

up a hillside by masked militants;

Whereas in the more than 2,300 days since Austin’s disappearance, no group has claimed responsibility for his

capture;

Whereas the Syrian government has never acknowledged detaining Austin and has denied the same to Austin’s parents;

Whereas officials of the United States believe Austin is alive

and the government of Bashar al-Assad or a group affiliated with it is holding him;

Whereas Austin Tice’s parents, Marc and Debra Tice, have

been diligent in their efforts to find their son, repeatedly

meeting with senior officials of the United States Government, the Syrian government, the United Nations, and

many others;

Whereas the Tices have traveled to the Middle East multiple

times, most recently in December 2018, seeking Austin’s

safe release, and Debra Tice spent four months living in

Damascus, Syria, for the same purpose;

Whereas the Tices have partnered with Reporters Without

Borders to launch campaigns with nearly 270 newspapers

and media organizations, highlighting Austin’s case in

their publications and on their websites;

Whereas institutions and organizations including Georgetown

University, Georgetown Law Center, the National Press

Club, the Committee to Protect Journalists, McClatchy,

and the Washington Post have collaborated to raise and

maintain public awareness of Austin’s detention; and

Whereas, on November 13, 2016, United States Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs, Robert C. O’Brien,

said that the United States Government believes Austin

Tice is alive: Now, therefore, be it

Resolved, That the House of Representatives—

(1) expresses its ongoing concern regarding the

capture of Austin Tice near Damascus, Syria, in August 2012, and his continuing detention;

(2) encourages the Department of State, the intelligence community, and the interagency Hostage

Recovery Fusion Cell to jointly continue investigations and to pursue all possible information regarding Austin’s detention;

(3) encourages the Department of State and

the Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs

to engage directly with officials of the Syrian government to facilitate Austin’s safe release and return;

(4) encourages the Department of State to

work with foreign governments known to have diplomatic influence with the Government of Syria; and

(5) requests that the Department of State and

the intelligence community continue to work with

and inform Congress and the family of Austin Tice

regarding efforts to secure Austin’s safe release and

return from detention in Syria.

The Associated Press

Parents of US journalist missing in Syria hopeful about fate

Marc and Debra Tice told reporters in Beirut that they have met U.S. officials including President Donald Trump and “they have each made a commitment to us that they’re determined to bring Austin home safely.”

Marc Tice said he was aware of 17 Americans that the administration had brought back from captivity or detention.

Austin Tice, of Houston, Texas, disappeared at a checkpoint in a contested area west of Damascus on Aug. 14, 2012, shortly after his 31st birthday. A video released a month later showed him blindfolded and held by armed men, saying “Oh, Jesus.” He has not been heard from since.

“We’re incredibly encouraged, and we’ve spent many hours, many days meeting all the senior officials in the United States government from the president down over the course of a number of months,” Marc Tice said.

Debra Tice said they were recently contacted by a number of credible individuals “who have shared information about Austin,” but she declined to elaborate.

Their comments came two weeks after U.S. envoy to Syria James Jeffrey said Tice is believed to be alive and held hostage in Syria. He didn’t say why officials believe this or who might be holding him.

In April, federal authorities for the first time offered a reward of up to $1 million for information leading to Tice, a former Marine who has reported for The Washington Post, McClatchy Newspapers, CBS and other outlets.

It’s not clear what entity is holding him, and no ransom demand has ever been made. An FBI poster released this year urges people to report any information that could lead to his location, recovery or return. The White House envoy for hostage affairs, Robert O’Brien, said last month that the administration is working to bring him home.

“What the president communicated to us was an absolute commitment to work very hard to bring Austin safely home,” Marc Tice said.

Parents of Austin Tice still fighting to bring their son home

Six years ago, American journalist went missing in Syria, but his parents hope US can secure his return.

Beirut, Lebanon – It was a Friday when Marc Tice received the call he dreaded.

“Are you sitting down,” the voice on the other end asked.

Marc’s son Austin, a freelance journalist, had been reporting from Syria and was scheduled to reach neighbouring Lebanon the previous Tuesday, but he had not been in touch.

Marc was anxious to hear from Austin, but when the phone finally rang, it was an official from the United States‘ State Department on the line.

The official informed Marc that Austin was missing. He had been picked up from a checkpoint near the Syrian capital, Damascus, on August 14, 2012, the day he intended to leave the country.

Since that call, made “six years, three weeks and a few days ago,” says Austin’s mother Debra, she and her husband have not rested.

They are currently on their eighth visit to Beirut, where they are knocking on doors and searching for clues which might lead them to their son. The Lebanese capital is about a two-hour drive from Damascus, and the closest city the Tices can reach while they search for Austin.

Debra hopes to obtain a visa from the Syrian authorities to allow her to move the search closer to the location where he was last seen.

On this trip, they feel more optimistic. The visit comes soon after a top official for hostage recovery in the Trump administration said the “US government believes Austin is alive”.

|

| Marc and Debra Tice hope the Syrian and the American governments will work together to free Austin [Bilal Hussein/AP Photo] |

The parents have flown in to put pressure on their government and, hopefully, to be heard by those in Syria they believe are holding Austin captive. No one has come forward to claim responsibility for his abduction.

The Tice family doesn’t know who exactly was responsible – and doesn’t care to know either. They are cautious, carefully weighing their words so as not to offend any side of the conflict. To them, it is not who has abducted Austin, but who returns him, that matters.

First denial, then a relentless search

Given a chance, every parent can expound on the achievements of their child. Marc and Debra Tice are no different. At a restaurant in Beirut, they talk about Austin’s skills, taking quick turns so that nothing is missed.

“He was first published when he was nine,” says Debra.

“He has always known what was important in life,” adds Marc.

“He is such a good swing dancer, he makes any woman dancing with him look beautiful,” Debra jumps in, gushing with pride.

During the first year of Austin’s absence, until late 2013, the family was in a state of disbelief. Every morning, they thought there would be a knock on the door and Austin would simply walk in.

Then, Marc and Debra decided that Austin was coming back. They just needed to play their part and ensure the Syrian and American governments were listening to them.

On their journey, they have established connections with hundreds of people in Lebanon, in Deraya – the Syrian suburb from which Austin had taken a taxi to cross into Lebanon when he went missing – and the US administration.

They started keeping “piles and piles of notebooks”, Debra says, to retrace his steps and understand what might have happened to their son. They connected with the families of other hostages and received sympathetic messages from other Americans freed in the past, including some who languished in the American embassy in Iran during the 1980 hostage crisis.

|

| Debra Tice says that Austin’s proof of life video was a missed opportunity [Mohamed Azakir/Reuters] |

“We had joined the horrible club, which no one must be a part of,” says Debra.

Being a parent of the missing brings its own changes to social life and routine. The couple’s friendships went awry because their friends didn’t know what to say to them, how to say it or how to help. They didn’t know what to offer, while Marc and Debra did not know what to expect.

“I go to the market and see these faces. I want to say – ‘look, I am here just for the tomatoes’,” Debra says.

It has been hard, they admit, but nothing compared with what their son must be enduring.

Austin’s proof of life came from a 40-second video posted online, a fortnight after he went missing. Marc and Debra Tice call it a missed opportunity.

“Every pixel of that video was seen and analysed. Who are the people? Is it fake or authentic? I know that was my son. I want to thank those who posted it because they were telling us Austin was alive. But why did no one say, contact them and begin a dialogue?” Debra says.

Can Trump bring back the American journalist?

The Tice family, from Houston, Texas, has now pinned their expectations on US President Donald Trump. For them, he is a president who walks the talk, and cares about the end result over protocol.

He has built a reputation for rescuing kidnapped Americans, they say, among them, Otto Warmbier, the University of Virginia student detained in North Korea.

In that extraordinary case, the Trump administration succeeded in bringing him home, though he was comatose and fatally sick from a never-explained brain trauma, and died shortly afterwards.

Following his death, Trump tweeted: “Otto’s fate deepens my Administration’s determination to prevent such tragedies from befalling innocent people at the hands of regimes that do not respect the rule of law or basic human decency.”

Marc and Debra are buying into the president’s words. They are convinced that Trump can and will strike some sort of a deal or understanding which facilitates Austin’s return.

They are also, through every press conference and interview, reaching out to the Syrian government. They hope, perhaps naively, that the two governments can forget their disagreements for the sake of an innocent life.

Debra visited Syria in 2014 and 2015. She walked through the souks of the capital city with a photograph of Austin, asking if anyone had seen him. She tried her best to seek help from senior figures in the Syrian government at a time when the US was backing the Syrian opposition forces.

On the record at least, President Bashar al-Assad‘s government has assured the Tice family that they are doing everything they can to find Austin. Does Debra believe the assurances? “I can’t not believe,” she says.

‘Austin meets us in our dreams’

Marc, Debra and Austin are caught up between complicated geopolitical calculations. Yet the parents are firm that they will not be defeated.

Deep in their minds, they say, their religious faith, as well as their love for their son and each other, sustain them.

At the end of the day, when Marc feels down, Debra carries on with a smile. They take turns.

“Austin is definitely coming home,” Marc says. “He meets us in our dreams.”

Debra describes one such meeting. “I am standing at the door, as I do, and there he is, Austin. He says, ‘Mom, now don’t make a big deal. I am back, shall we go inside?'”

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA NEWS

Missing American reporter Austin Tice is believed to be alive, says U.S. official

By CBS NEWS November 14, 2018, 3:55 PM

The U.S. government strongly believes Austin Tice, a Marine-turned-reporter who vanished in Syria in the summer of 2012, is alive and being held captive in the war-torn Middle Eastern country, according to a senior State Department official.

“I want to make it very clear that the United States government believes Austin Tice is alive,” U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs Robert O’Brien told reporters on Tuesday. “We are deeply concerned about his well-being after six years of captivity.”

In an event hosted by the National Press Club, O’Brien said the State Department is spearheading an investigative and diplomatic multinational effort to locate the missing journalist and secure his release. The special envoy called on the Russian government — which has provided significant financial and military assistance to the regime of Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad — to take part in this humanitarian cause.

“There are plenty of areas of disagreements between the United States and Russia at this time,” O’Brien said. “One of the things that both Russia and the United States should agree on is that innocent Americans, or innocent Russians for that matter, should not be held hostage and should not be held against their will.”

Since 2011, Syria has been embroiled in a bloody and convoluted war involving forces loyal to President Al-Assad, moderate rebel groups, Iranian-backed Hezbollah cells, ISIS and Russian and American military units.

Tice, a former Marine Corps captain who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, traveled to Syria in the spring of 2012 to document the nation’s then-young civil war as a freelance reporter before starting his final year at Georgetown Law School. After filing award-winning reports for various outlets — including McClatchy, The Washington Post and CBS News — Tice disappeared in Aug. 14, 2012.

Five weeks after his disappearance, a video surfaced showing an alive and blindfolded Tice surrounded by a group of unidentified armed militants.

In April of this year, when the FBI announced a $1 million reward for information “leading directly to the safe location, recovery, and return” of Tice, CBS News reported that although some believe he was captured by Syrian regime forces or pro-government militias, the circumstances surrounding Tice’s disappearance remained a mystery.

Although he said he could not disclose intelligence information that supported the government’s assessment that Tice was alive, O’Brien, the State Department envoy, highlighted the fitness of the combat veteran as a beneficial characteristic during this type of ordeal.

“He’s got the toughness of a Marine. And I’m sure that’s sustaining him through these incredibly trying circumstances,” he said.

O’Brien noted that Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has been “intimately” and “actively” involved in the case and added that, along with U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley and National Security Adviser John Bolton, America’s chief diplomat has met with Tice’s parents, Marc and Deborah Tice, on several occasions to brief the couple on any new developments.

Before the end of the year, Marc and Deborah Tice will undertake their seventh trip to the Middle East to apply for a visa to enter Syria. There, the couple hopes to be closer to Tice and reach out to whomever may be holding him captive.

“We continue our relentless effort to find the key that will open the door for Austin’s freedom,” Mr. Tice said.

Trump Administration: Effort to return captured journalist counts on U.S. reporters

FORT WORTH STAR-TELEGRAM

NOVEMBER 12, 2018 09:00 PM,

UPDATED NOVEMBER 13, 2018 11:18 AM

By McClatchy

WASHINGTON

The Trump administration, known for its public feuds with the media who cover it, on Tuesday joined with major media organizations seeking to bring home missing foreign journalist Austin Tice.

Tice disappeared more than six years ago reporting on government turmoil in war-torn Syria.

Speaking at the National Press Club Tuesday, Trump’s special envoy for hostage affairs, Robert O’Brien, said the administration believes Tice is alive, and White House officials are working with journalists and news organizations seeking to bring him home.

“We have great FBI agents that have been following every lead, every clue that we can discover about Austin,” said O’Brien. “But journalists have been working their own networks and have been bringing leads and information to us, and we are grateful for that.”

O’Brien said Tuesday that Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has been “intimately involved” in Tice’s case, and that the administration is “deeply concerned” about his well-being after years of being held captive.

“Pariah states like Iran, terrorist organizations around the world continue to take Americans hostage or unjustly detained… because they believe they can extract some sort of concession from the United States… and I can tell you that is not going to happen, “ said O’Brien.

“We are not going to be terrorized, our reporters are going to continue to go to the toughest places on earth and report,” he added.

Earlier this month Trump’s White House revoked press credentials for a CNN reporter — once again igniting the tense relationship between American media and a president who referred to it as the “enemy of the American People.”

O’Brien was joined by Tuesday by Tice’s father, Marc Tice, as well as McClatchy President and CEO Craig Forman, McClatchy Company Chairman Kevin McClatchy, National Press Club President Andrea Edney and officials from the Washington Post and Reporters Without Borders.

They detailed plans for a “Night Out For Austin Tice” on May 2 to raise money for a cash reward for information leading to Tice’s safe return.

The effort involves restaurant partners who will donate a portion of their profits from customers who patronize their establishments on the eve of World Press Freedom Day on May 3. The day has been designated by the United Nations to remind governments of their agreement to support and protect the right to free expression.

The FBI has offered a $1 million reward for information leading to Austin Tice’s safe return. Proceeds from the “Night Out For Austin Tice” aim to add enough to double the reward to $2 million.

O’Brien is a California lawyer who served as an attorney for the U.S. Army Corps Reserves.. Earlier this year he was tapped by the Trump administration to help bring home American hostages held overseas, including journalists like Tice.

The position was created by President Barack Obama in 2015. Tice’s parents told McClatchy in August, however, that the current White House has been a more aggressive partner in working to bring their son home. They spoke personally with Trump at a dinner honoring Washington media earlier this year.

“We know it’s important to [Trump] to bring Americans safely home,” Debra Tice told McClatchy near the six year anniversary of her son’s disappearance in August.

Tice said that “we’re off to a good foot” with the administration.

Austin Tice, a native of Houston, Texas, and a former Marine, worked as a freelance journalist for the Washington Post and McClatchy while reporting from Syria.

He was detained en route from Syria to Lebanon on Aug. 14, 2012. He was last sighted six weeks after he was detained, in a video that showed him being guided up a rocky hill by a group of armed men.

National Press Club President Andrea Edney, left, and U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs Robert C. O’Brien, right, speak at the National Press Club Tuesday, Nov. 13, 2018.

Andrea Drusch is the Washington Correspondent for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. She is a Corinth, Texas, native and graduate of the Bob Schieffer School of Journalism at Texas Christian University. She returns home frequently to visit family, get her fix of Fuzzy’s Tacos and cheer on the Horned Frogs.

|

June 22, 2016

![]()

4 hostage families make a plea: Bring home Austin Tice

An essay by Diane and John Foley, parents of James Foley; Ed and Paula Kassig, parents of Abdul-Rahman Peter Kassig; Carl, Marsha and Eric Mueller, parents and brother of Kayla Mueller; Shirley and Arthur Sotloff, parents of Steven Sotloff.

One year ago this week, following the torture and killing of two of our American journalists, James Foley and Steven Sotloff, and two of our American humanitarian aid workers, Peter Kassig and Kayla Mueller, President Barack Obama made a commitment to improve our government’s dismal record on the return of American hostages.

The president ordered a new government hostage policy, accompanied by a presidential policy directive, representing a much-needed effort to clarify and coordinate the government’s response to hostage-taking. The directive outlines the processes by which “the United States Government will work in a coordinated effort to leverage all instruments of national power to recover U.S. nationals held hostage abroad, unharmed.”

Austin, a freelance journalist, Marine veteran and Georgetown law student, has been held hostage in Syria since August 2012. His safe return will satisfy a significant and necessary measure of the success of the new policy. Austin is the only American reporter being held hostage anywhere in the world, according to Reporters Without Borders. At the recent White House correspondents’ dinner, President Obama committed “to fight for the release of American journalists held against their will.” We were stunned and disheartened when the president chose not to refer by name to Austin, the only American news journalist being held against his will.